Project Description

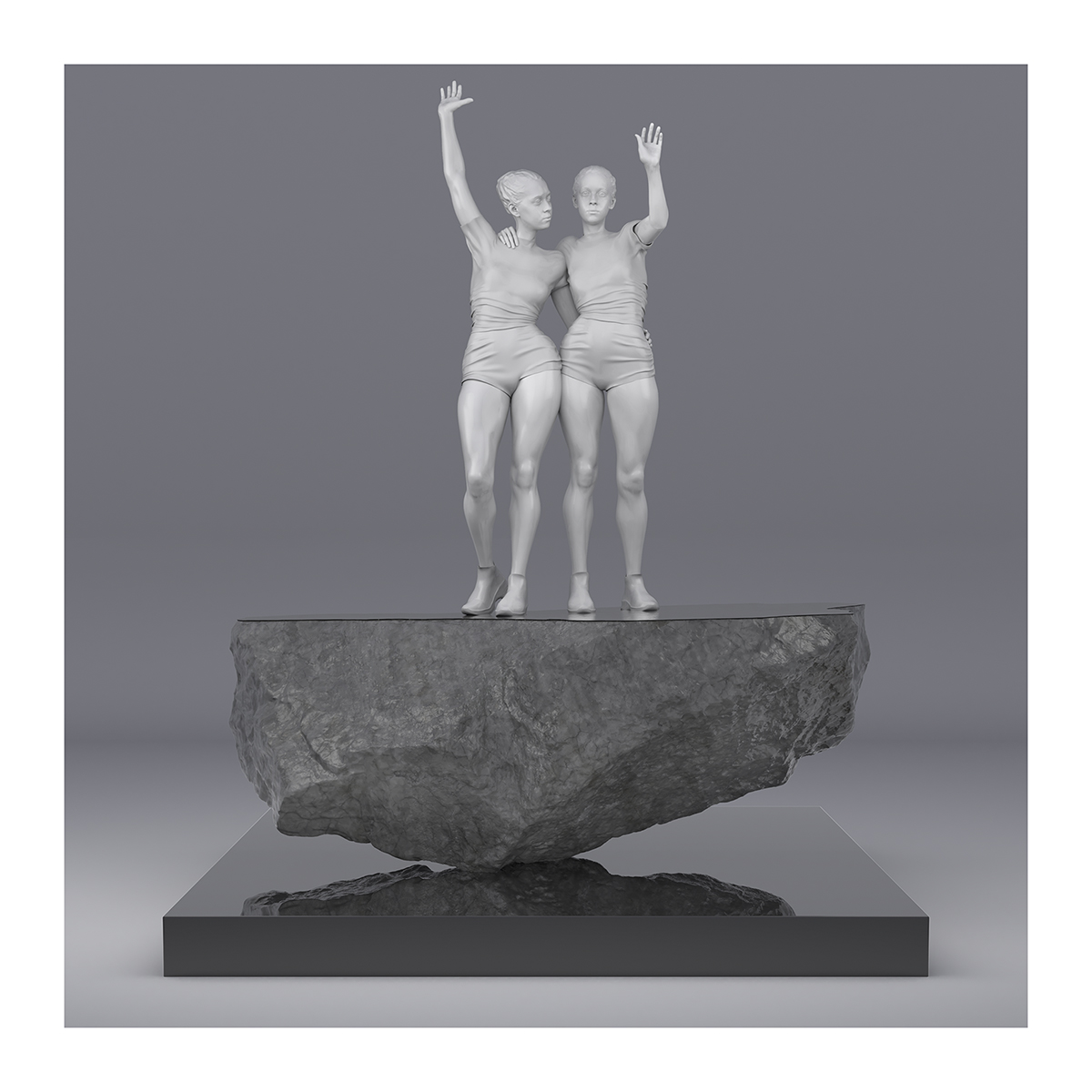

Reloaded Venus. The Silence of Victory. V004

Sculpture in Public Spaces

Body : Bronze. Height 170 cm

Rock : Bronze + Painted Finish. Height 90 cm

Base : Polished Steel. Height 25 cm

Total Height : 285 cm

Limited Edition 6

Reloaded Venus. The Silence of Victory. V004 – 1200 pixels width imagefile

1. The History of Sculpture in Public Spaces: From Classical Statuary to Contemporary Works

Sculptures in public spaces have evolved over centuries to embody aesthetic, political, and spiritual values.

Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Public sculptures were often religious or honorific. In ancient Greece, statues like Athena Parthenos embodied deities and civic ideals. During the Middle Ages, sculptures on cathedrals (e.g., gargoyles, saints) guided and impressed the faithful.

Renaissance and Classical Periods: Sculpture became a tool to glorify power. Equestrian statues, like that of Marcus Aurelius in Rome or later Louis XIV at Versailles, expressed authority and prestige.

Modern Era: With the rise of revolutions (American, French), public monuments took on a democratic dimension, exemplified by The Statue of Liberty (1886).

Contemporary Period: The 20th century saw a break with figurative traditions. Works became abstract or interactive, such as those by Alexander Calder (stabiles and mobiles) or Anish Kapoor, integrating public engagement into the experience.

2. The Political or Social Stakes of Public Commissions

Public sculptures often reflect the tensions of their time:

Political: Public commissions are sometimes tools of propaganda. Statues of leaders, such as Soviet monuments to Lenin, served to construct national myths.

Contestation: Sculptures can also be objects of debate. The contemporary movement to remove statues tied to slavery histories (e.g., those of Cecil Rhodes) shows how these works can crystallize historical tensions.

Inclusion and Participation: Today, public commissions tend to be more collaborative and democratic, aiming to represent diverse identities (e.g., 4th Plinth at Trafalgar Square).

3. The Role of Materials and Durability

The materials chosen for public sculptures respond to practical, aesthetic, and symbolic imperatives:

Durability: Sculptures made of bronze or stone, like classical monuments, were designed to withstand the test of time.

Innovation: Contemporary works explore less traditional materials (industrial metals, glass, plastics, LED). Example: the light installations by Olafur Eliasson.

Environment: Ecological concerns influence creation, with works designed to be biodegradable or integrated into ecosystems (e.g., the reef sculptures by Jason deCaires Taylor).

Interaction: Modern materials often enable interaction and participation, such as the reflective surfaces of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate (Chicago).

4. Famous Examples in Public Spaces

The Statue of Liberty (Bartholdi, 1886): A symbol of emancipation and welcome in the United States.

Maman (Louise Bourgeois, 1999): A giant spider installed in public spaces like Bilbao or Ottawa.

Cloud Gate (Anish Kapoor, 2006): Sculpture emblem of interactive public art. Chicago.

The Stelae of the Holocaust Memorial (Peter Eisenman, Berlin, 2005): Abstraction and collective memory.

Seven Magic Mountains (Ugo Rondinone, Ivanpah Valley, California. 2016) – Installation of rocks found on site, painted and balanced, more or less precariously.

5. Why Avoid Overly Provocative Sculptures in Public Spaces?

Public sculptures, as creations accessible to everyone, reach a diverse audience. Several arguments justify a degree of restraint in their content:

Respect for Cultural Diversity and Sensitivities

Public spaces are shared by communities with varying values, beliefs, and traditions. A work that is too provocative may be perceived as an attack on collective norms or specific groups.

Social Function of Public Space

Public art is often expected to contribute to harmony and inclusion. Offensive or shocking sculptures could provoke social tensions instead of enriching communal spaces.

Institutional Context

Public sculptures are often commissioned or approved by public authorities, who are accountable to their citizens. Controversy can lead to political pressure and damage the reputation of the supporting institutions.

Risk of Vandalism or Rejection

A controversial work is often a target for vandalism, reducing its impact and increasing maintenance or replacement costs.

Example: Paul McCarthy’s Tree

In 2014, American artist Paul McCarthy created a monumental inflatable sculpture titled Tree, installed in Place Vendôme, Paris. The abstract work, representing a 24-meter green “tree,” quickly sparked outrage because many associated its shape with a sexual object (a butt plug). Reactions: The sculpture immediately caused a media and social media uproar, with some viewing it as an insult to the elegance and cultural heritage of Paris. The artwork was vandalized and deflated within days by opponents. McCarthy himself was physically attacked by a passerby, accusing him of corrupting public values. Consequences: The incident highlighted tensions between artistic provocation and public expectations of art in shared spaces. While some defended it as a bold artistic statement, others criticized it as disconnected from citizens.

6. Conclusion: A Necessary Balance

While provocation can be a powerful tool for reflection in art, public sculptures require particular attention to social and cultural contexts. Their impact goes beyond the artist’s intent, directly affecting the daily lives of citizens. In this sense, exhibiting art in public spaces demands a shared responsibility between artists, institutions, and society.